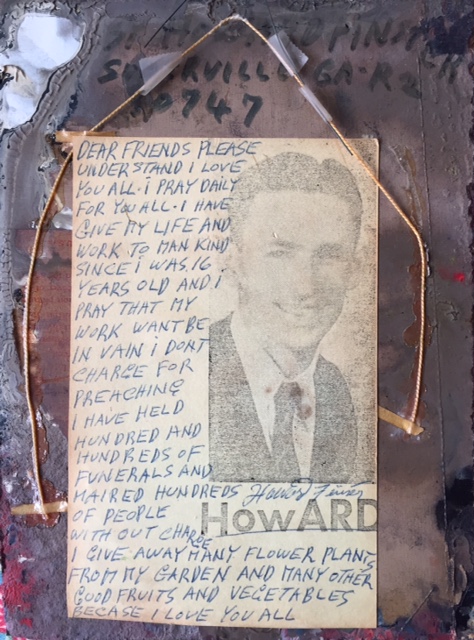

I was sitting at the counter in my grandmother’s kitchen, looking up at the small piece of art that hung above the toaster. I had seen it there every visit since I was born, but this time, I knew more about the man who had painted it and 46,990 other pieces. This one seemed to have been made with sheet metal, shards of a mirror and vivid paint. It was titled “Vision of Strange Seens,” numbered “1000 and 416” and signed “Howard Finster.”

You could say I’ve known who Finster was for all of my life. But after visiting the “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” exhibit at the High Museum, I was now trying to decode the labels that he and his art were given.

The description of the High’s exhibit begins, “Self-taught artists — variously termed folk, primitive, visionary, naïve, outsider and isolate — have played a significant role in the history of modernism, yet their contributions have been largely disregarded or forgotten.” The museum refers to the artists as “outliers,” emphasizing that the category is defined by spatial relativity, but the term “outsider” is presently often used. As I did more research, I noticed both the widely perceived power and insignificance of assigning labels and sorting by category. I also became more and more drawn to the creators that are grouped using that paradoxical term: outsider.

The inside and the outside, the mainstream and the margins, blurred intersections and highlighted differences, outsider artists make the everyday person more deeply examine these past conceptions, and those of art, of categories and of creative intent. Even their name, or at least the one that’s currently most widely used, blurs boundaries and raises the question: Is someone still an outsider if they’re the center of attention?

While a narrative of re-examining the labels that attempt to define creators has begun, debates and discussions are sparked outside of the sphere of outsider artists. What those who go by that still-lasting label think about their own place in the art world is little explained or acknowledged: an ironic truth of the mainstream art world, its critics and its followers.

The term outsider art doesn’t only encompass the work of self-taught artists, folk artists or “primitive artists.” In truth, it doesn’t have a set definition. What curators, historians and other art experts agree on is that outsider artists are grouped together not by their style, but because they reside in the margins (however one may define that term) of the art world and, going beyond the creative community, are often part of marginalized communities. But is it really for them — those who are so rooted in the mainstream — to define?

Reporting on outsider artists is certainly not novel. The art world has been enraptured with outsider art for decades. However, the vanguard side of the art spectrum may be seeking a certain look when outsider artists are led into the mainstream art tradition. Outsider artists who gain expansive recognition are often “discovered” by a member of the front-and-center art world, however Christopher Columbus-esque that sounds. This recurring action does expand mindsets of the public, but outsider artists’ art missions rarely include worldwide fame or prominent museum exhibits. Some creators don’t even label their own work as art.

Outsider artist Clementine Reuben Hunter once said, “I’m not an artist, you know, I just paint by heart.” R. A. Miller, a Georgian artist, declared that his work was “junk,” according to the Georgia Museum of Art. This mindset, however, is one path that has led to the creation of the art environments so often associated with outsider artists. In some people, the thought that their artwork is unworthy of museum walls, or serves a purpose outside of being admired, has prompted them to fill their own world with their creations.

The questionability of the relationship between insider and outsider art notwithstanding, it’s evident that outsider artists have made a profound impact on mainstream art, the definitions and perceptions of art, and the mindsets of today’s art viewers.

In the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, outsider art was characterized by spiritual visions and portrayals of farm life. This image was partly shaped by the mainstream art scene: romanticization of impoverished or mentally ill individuals in the South was wanted, and so artists that fit into this fantasy were highlighted. On the other hand, the recognition these artists gained isn’t only the product of an exploitative art market. The rise in interest directed toward outsider artists resulted in an expanded definition of “art” and spread new ideas from the work of skilled artists. This illustrates a dual result of the vanguard art world’s deliberate actions.

Outsider art and the South have always been strongly linked. This connection originated in part out of the southern United States’ sparsely populated areas, which are often marginalized with limited access to big city resources. The Appalachian mountains have been a rich source of folk art, holding skills passed down through generations. The history of slavery also plays a large part in the South’s art history, among countless other aspects of today’s society. Georgia, specifically, is known as “a bastion of self-taught art,” according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia, and part of the strong geographical relationship that bonds outsider art and the American South.

After an interview with Katherine Jentleson, Atlanta’s High Museum’s curator of folk and self-taught art, I knew immediately her position on the terms given to this range of artists. “I don’t like to have a fixed definition of outsider art,” she said. She added the word “outsider” lacked the fluidity of the High’s preferred “outlier.” She likens the relationship between outsider/outlier and mainstream art to “the relationship between two points in space … always shifting.” She also shed light on the reasons behind some common themes and circumstances of outsider artists.

The tendency among outsider artists to create art environments, for example, is shown to be a result of shared feelings toward more traditional ways of art exhibition. Members of marginalized communities with no formal art training may feel their art isn’t valued in a museum, or don’t even classify it as art. Yet the need to create persists, so some fill their home with the products of their efforts. Now we have such captivating evidence of this phenomenon as Nellie’s Playhouse and Paradise Garden. Outsider artists, such as all the artists listed above, often find themselves in their creative primes in the last years of their lives; this is no coincidence. Since many are self-taught, lacking the opportunity of art school, they also lack the freedom to create art in their working primes.

Finally, Jentleson offered her thoughts on visionary artists, or those who create art for predominantly spiritual reasons, like Finster, who “preaches through his art,” and Alpha Andrews.

“It serves as a justification for their community,” she said. Though the people that surround an artist might not think art a worthwhile pastime, religion is a different story. Jentleson emphasizes that, although one can see general patterns among the circumstances and stories of these artists, their experiences are both unique and repeated in different forms within the lives of artists worldwide.

Since outsider artists are, in a way, defined by mainstream art, specifically their location outside of the “artistic establishment,” outsider art changes as insider art does. The strong outsider art force here in Atlanta is one that, similar to Howard Finster’s Paradise Garden or Nellie Mae Rowe’s Playhouse, can’t be confined to museum walls. Atlanta is a center of street art, the most public form of visual art. According to Brian Chidester of The American Prospect, street artists fall “under the larger umbrella of ‘outsider’ art by virtue of their anti-establishment sensibility” and tendency to be self-taught. The Atlanta Folk Art Park in downtown Atlanta has been newly restored and displays the works of such artists as Howard Finster, R.A. Miller and Saint E.O.M., the creator of the culturally blended art environment Pasaquan. If part of the evolved generation of outsider art is street art, then Atlanta is the place to witness it.

In all, one thing remains clear: The distinction between insider and outsider art is a controversial topic, and is a differentiation that should be interpreted with an open mind. We should be critical of any artist categorizations, for they are often fraught with generalizations. Labeling a large group of individuals never gives them their full justice.

Below are some influential Georgian outsider artists whose impact is felt far beyond their mid-century primes. They share a peak time period and extremely detail-oriented styles. Specific connections between combinations of the artists include religious themes, rural inspiration and art environments — both Finster and Rowe have expanded their studios into immersive museum-like spaces.

Howard Finster (1916-2001)

Born in Northern Alabama, but later settling in Summerville, Georgia, Howard Finster is arguably the most well-known icon of Southern outsider art. He incorporated Appalachian culture, religiosity and pop culture celebrities into his text-laden pieces. Although he died in 2001, his legacy lives on in Paradise Garden, his expansive art environment. To learn more about the man who was once “the most famous artist in Georgia,” I talked to Tina Cox, the director of Paradise Garden. “Howard Finster was a really, really good person,” she said, repeatedly emphasizing his strong moral guidance and willingness to help others. “[People who met him] all use one four-letter word: Howard Finster is love.”

Cox stated that the reason for his international fame was his ability to put love into his work, and to make others feel it strongly. Cox seemed indifferent to the labels often given to Finster and his work. “Vernacular … outsider, they’re just simple reference[s],” she said, “they all have the need to express themselves … that’s the thing they have in common.” I learned that the angels I saw in my grandmother’s small Finster piece were motifs present in almost all of his work, and that they symbolized Abigail, his late younger sister. On the back of the piece is a note that starts “Dear Friends please understand I love you all,” evidence of Cox’s descriptions of Finster’s kindness. When I went to visit Paradise Garden, I understood why Cox said his wish was to “put one of everything in the world in it.” The Garden is a testament to the creators and innovators of the world — the people he admired most — and the home of his profuse goodwill.

Nellie Mae Rowe (1900-1982)

Nellie Mae Rowe’s work alludes to Australian aboriginal dot paintings. Her style is bright and surreal, and her works are riddled with symbols of her ancestry, childhood, values and future. She was an African-American woman living in the South at the turn of the century and spent her childhood working in the fields of rural Georgia. Already, the odds were stacked against her, but her parents, both creators themselves, supported her work and she described her childhood fondly. In fact, possibly the biggest influence on her art was her childhood. As a middle-aged woman, disillusioned with her life of marriage that she was bound to at age 16, Rowe built her own identity and independence through art. Reverting to her favorite childhood pastime of drawing, she recrafted her life as a creator. She reimagined her childhood playhouse in aspects of her home, studio and a kind of museum exhibit, which she decorated with her dolls and sculptures and named “Nellie’s Playhouse.” Strong feminist themes unite her body of work, yet one must look closely at the symbols she employs to see this. In the last years of her life, she only increased her creative output; as the Souls Grown Deep Foundation puts it, “just as she had taken control of her life, and used her art to define and explain it, she prepared to take control of her death.”

Ulysses Davis (1914-1990)

In contrast to Hunter and Miller mentioned above, Ulysses Davis of Savannah, Georgia, recognized his work as art, calling it his “treasure.” His designs are polished and precise, yet he used only scrap wood and often didn’t make primary designs before honing his sculptures with a hatchet. His work includes busts of 40 U.S. Presidents and hundreds of animal, spiritual, metaphorical, abstract and functional figures. Based off information provided by the American Folk Art Museum, Davis was a barber by profession and this contributed to his style and technique; he sometimes used tools from his shop to do detail work. Davis differs from the other artists mentioned in style and medium, but like them, he conveys religious themes, possesses a Southern heritage and comes from a marginalized community: he was an African-American man living in the Jim Crow-era South.

Alpha Andrews (b. 1932)

Like Nellie Mae Rowe, Alpha Andrews grew up working Georgia cotton fields. She worked, and works, hard to support her large family, taking on many jobs in addition to her career as an artist. Her work mirrors Finster’s attention to often fantastical detail and Rowe’s vivid color choices. In another similarity to Rowe, she uses animals as a motif throughout her work and writes short verses amid the intricate detail. The final products are mosaic-like and rest on the fine line between the real and the surreal. Her pieces mix rural life, religion and Biblical and Southern geography — the result a crafted world all her own.

For teens interested in outsider art of the past, visit the art environments Paradise Garden, Nellie’s Playhouse and Pasaquan.

Interested in making your contribution to the outsider art of the future? Spread messages of social change in Atlanta’s Krog Street Tunnel. Explore your outsider art surroundings throughout Atlanta’s rich street art scene.

This is fascinating! Great job.

This is so interesting! I’ve always wondered about the art park in downtown Atlanta, so now I know!