Racism is one of the scariest words I know.

It has changed the way people perceive me, offer opportunities, treat my family and thousands of other things that would take 15 more years for me to think about. I’ve always been taught that racism is as bad as it gets. Society creates diversity mixers and practices integration to try and unify different races. But what about unifying the different shades of people within a race?

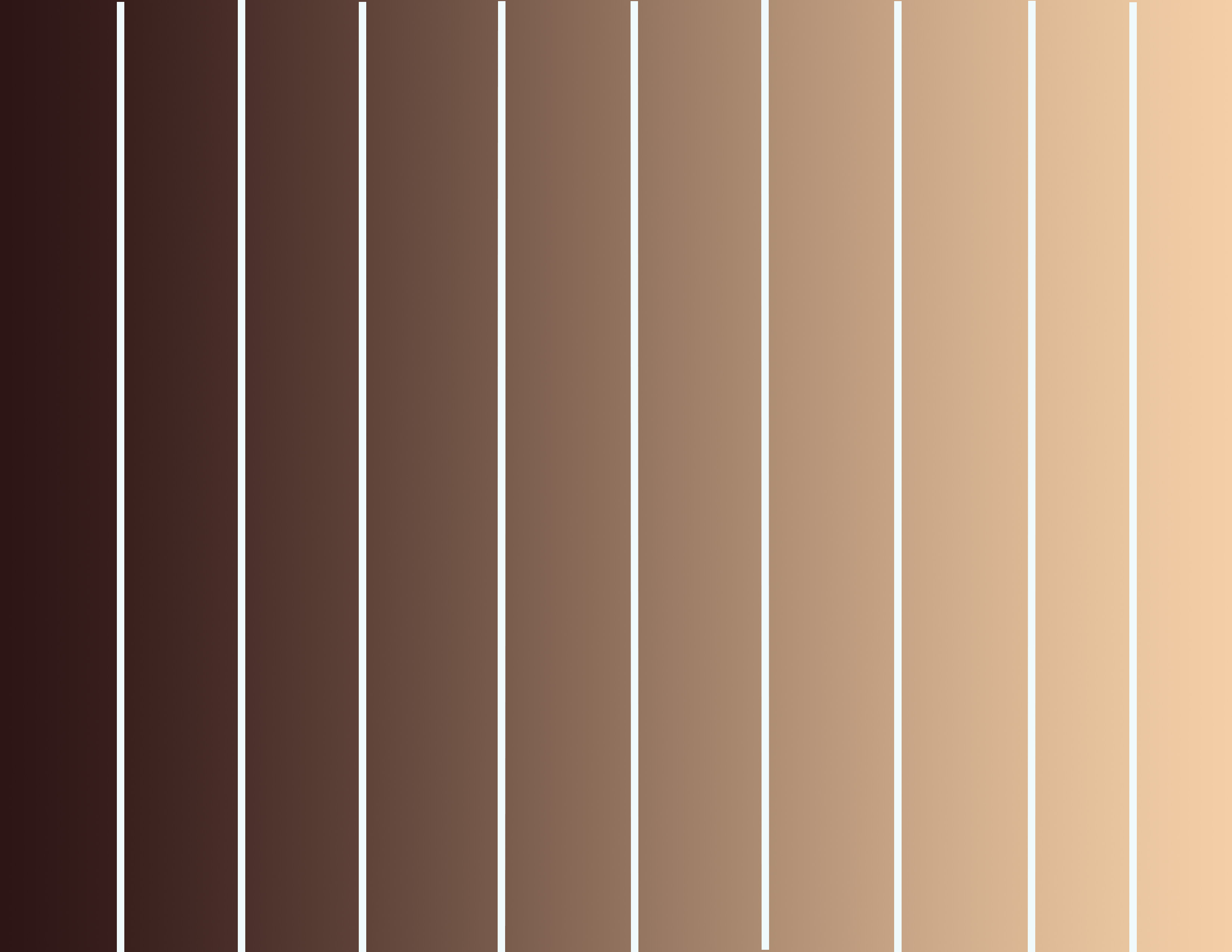

Colorism is the prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial groups. My parents always tell me how important it is to be mindful of racism, but society is digging a deeper hole without even realizing it. Colorism not only encompasses racism, but propels it. As we move forward to eradicate the large-scale issues, we are creating more problems that occur within our own communities.

Colorism is simply institutionalized racism that comes with an instruction manual for how we should and shouldn’t perceive people based on the color of their skin – within a racial group. Darker skin tones are often seen as threatening or “dangerous,” while the lighter skin tones are assumed to be mild-mannered and sweet. According to a 2006 Cornell Law School study, “Even with differences in defendants’ criminal histories statistically controlled, those defendants who possessed the most stereotypically Black facial features served up to 8 months longer in prison for felonies than defendants who possessed the least stereotypically Black features.”

In addition to that, a University of Georgia doctoral student’s 2006 study showed that employers prefer light-skinned black men to dark-skinned men, regardless of their qualifications. And a 2013 study and doctoral article entitled “The Psycho-Social Impact of Colorism Among African American Women: Crossing the Divide” focuses on a group of African-American women who are on a scale of either being light, brown, or dark skinned. Their experiences were analyzed on a larger scale and put into broader themes. After the analysis was done, the mental state of the women was addressed. “The findings suggest that women of different hues have unique experiences based on their skin tone, and that these experiences influence how they feel about themselves, and how they interact with others.”

There are many different perceptions “of color” when it comes to gender. In the black community, the men of darker shades are viewed as “thug” or “gangster” while lighter-toned men are the “scholars” and “college graduates.” Similar assumptions are made for women. Those who are darker-skinned are stereotypically viewed as “loud” or “ghetto,” while light-skinned women are assumed “classy” and “educated” angels. According to The Root, “researchers at Villanova University found in 2011 that light-skinned women were sentenced to approximately 12 percent less time behind bars than their darker-skinned counterparts.”

As a proud ambassador for the black community, I have experience with colorism in a variety of ways. Sure, I’m lighter than your average black girl due to my Asian descent, but I am black nonetheless, and colorism has played a huge role in my life. Growing up, I always wanted to be lighter. I hated my brown skin and curly hair, and desperately wanted the flawless golden skin and pristine primped hair I saw on television. I wasn’t able to understand why they were idolized for having those characteristics while what I had was (in my opinion) frowned upon. The underrepresentation of dark-skinned girls with curly hair on television was a constant reminder that darker shades were a no go when it comes to the media.

Despite being older and more accepting of who I am now than I was five years ago, I still remember specific instances in which I was harassed or degraded for being darker than other young men. In elementary school, my dream was to star on the school news program. Public speaking had always been a passion of mine, and being new to the school gave me an incentive to join a new organization and make friends. I arrived to the news show audition eager, so eager that I didn’t notice the lack of representation in the room. When my turn to read came around, I was stopped by a light-skinned girl with green eyes and curly brown hair. “Don’t you think it’s a little weird for you to be doing this?” she asked me. I thought maybe because I was new and she didn’t know me well she thought it was odd for me to be branching out and joining extracurriculars. When I shook my head no she replied, “I mean, you are too dark to be on camera” and sauntered off. To this day, whenever I approach a media project or an onscreen opportunity, I remember that awful girl who not only ruined my audition but also the confidence I had in my skin tone and what it represented.

Even so, as I got older, I learned to embrace my skin and combat the loathing and oppression I received from ignorant haters who just happened to stand between me and self-acceptance. I realized I was one of the luckier ones in my community, even though I have experienced my fair share of shade-induced bullying. The classic “Oreo” jokes never fail to amuse the imbeciles of my generation; however, I have never experienced extreme racial degradation in the way that many people darker than me do on a daily basis. The darker-toned people in my generation are viewed as less just because pigment is more abundant for them. As I gained more and more exposure to discrimination, I realized that torment and taunting I had never even witnessed before was happening all around me, which undermines the hundreds of years of movements and protests by our ancestors to prevent that very cruelty.

For hundreds of years, we have been fighting to win one battle, but we have been so distracted that we failed to realize that smaller battles began to arise. Racism is a huge pill to swallow, but before we can even attempt to address it, communities must resolve their own internalized oppression. How can one say they are “not racist” if they hate on a woman of lighter skin just because, or if they resent darker-skinned women because of stereotypes created by people whose sole purpose is to destroy our race? If we can’t be secure in our own communities, how can we ever be united as a multi-racial society? For racism to be eradicated, I believe that unity is necessary.

As a young black woman in America, I experience the impact my skin tone has on my life everyday, and I shouldn’t have to. I shouldn’t wake up in the morning terrified that I won’t make it home because someone “disagrees” with the shade of my skin. I shouldn’t feel threatened every time someone mentions the perfect light-skinned girl. I shouldn’t have to stress about opportunities passing me by because I’m not light enough to be considered educated or dark enough to be considered underprivileged. For example, the Brown Paper Bag Test was used in the early 1900s when the color of a brown paper bag was used to determine the privileges granted to specific individuals — for example sorority and fraternity membership.

My education, my relationships, my life shouldn’t be able to be destroyed by my skin tone. And neither should anyone else’s. Skin tone is something we are given by birth, and with it we receive the culture, stories and significance that lies within. None of us should feel like our skin tone was an unfortunate pick.

Movements like MERI which are aimed toward ending racism and islamophobia and IMADR which focuses on eradicating all forms of racism and discrimination are very important. They not only encourage inclusion but also practice acceptance. We must address the issues and possible mechanisms of enacting not only awareness but change. However, if we are so caught up in who’s lighter than whom and whether my skin value is worth more than yours, we will never be able to tackle the issues that plague our society every day.

We have to be better than this. We cannot let something as juvenile as our appearance justify the countless moments of harassment and torment some people experience. It’s time for us to get out of the mirror and into the streets. Without colorism we are one step closer to ending racism, and I think this step is one that the shoes of my generation were made to take.

Pictured: left to right.: Kwatcho Mahinanda, 16. Najah Reed, 15. Alexis Jones, 15. Niya Baskett, 15. Avion Levermore, 16. Renee George, 17. All photos were contributed by the girls in them.

Pictured: left to right.: Kwatcho Mahinanda, 16. Najah Reed, 15. Alexis Jones, 15. Niya Baskett, 15. Avion Levermore, 16. Renee George, 17. All photos were contributed by the girls in them.

Sydney, 15, attends Rockdale Magnet School for Science and Technology and loves writing and musical theater.