Riven Mendoza, 17, is the valedictorian of the Class of 2017 at Creekside High School. They* are a first-generation citizen whose parents immigrated from Mexico to the United States before they were born. Riven sat down with VOX to discuss the realities of being a first-generation citizen and a Mexican valedictorian at a predominately black school. Here’s what they had to say:

Can you tell me about being a first-generation citizen in high school?

RM: It’s a big deal when you’re coming from immigrant parents, [being] the first born into America. There’s a lot of pressure, as the value of education is so high that it sometimes is overwhelming. You have to excel because your parents [who] came from another country don’t speak the language and can’t network at all.

How has being a first-generation citizen affected your success in high school?

RM: Teachers like to say that because I am a minority, I have to do certain things to “prove them wrong” and that’s just increased pressure.

What are some challenges you’ve faced in high school, academically and socially?

RM: So, when it’s been established by the entire class that you’re the top kid, it’s very stressful. Say there’s a test and the teacher says, “Only one of you got a perfect score.” [The class] would immediately look at you, but you’re like, “I swear I got an 80,” and you’re OK with that because you passed. I feel really bad when kids in my graduating class say, “I wanted to be valedictorian but since you’re at the top position, I don’t feel like doing it anymore.” But, no, you have the capability to be where at I am. They see me as the most perfect student, and it’s really stressful.

How do you think your high school experience or struggles would have been different had you not been a first-generation citizen?

RM: So, if my parents had been born here and I had been second-generation, it would have been a lot easier because not only would they know English better, they would understand how the whole college process is, like how to do your FAFSA, how to pull up your transcripts — all of that. I think that would have been much easier because when my sister graduated from high school [Class of 2015], it was very, very overwhelming.

When you have to translate as children on the phone with an admissions officer, you’re talking on the phone in English and then your parents are in the background in Spanish, trying to listen, and you have to go back and forth. There’s a long pause on the phone because your parents are trying to ask you a question and they [admission officers] think you’re done talking, and they hang up.

I find it really disrespectful when English speakers look down on my parents for trying to speak English. They work so hard and they’re trying to give us a better life, and they [English-speakers] think they’re uneducated, when they would have gone to college back in Mexico if they could have, but it’s so expensive there.

Do you find large cultural barriers being Latinx when the majority of students at your school are black?

RM: Because I’m not dark like other Latinx students, some black students assume that I am white, but I’m not. I remember this girl said, “Are you French, because you look French?” One time, this black girl was pointing out the white students in the hallway and she pointed at me. Plus, the majority assume that we all [Latinx students] are Mexican and speak fluent Spanish. They’ll go up to me and ask, “Are you Mexican? Can you speak Spanish?” My Spanish is not for your entertainment.

Have you been discriminated or ostracized for being a minority at your school?

RM: In ninth grade gym class, there was this boy who would always call me and the other Latinx students “mamacita,” and that was one of the most disgusting things ever told to me because Latinx people are not meant to be fetishisized, especially young girls.

In my SAT prep class last year, a teacher was telling this story about a family that had lighter skin and married each other, causing problems within their family. He said that their skin color was my skin color and pointed it out to the class. Then he said, “No offense, I just wanted to use your skin color as an example.” I found it very offensive that he would use my skin color as an example for incest.

How has going to a Title I school affected opportunities and accessibility for you?

RM: I was in middle school when a librarian told me, “You should apply to a private school when you go to high school because you would really thrive in that environment.” I don’t have the economic opportunities to go to a school like that. I really benefit from smaller classroom sizes. Math is a difficult subject for me, and if I went to a different school I could have a math teacher [who] could actually help me. I have amazing intellectual abilities, but I’m not given opportunities because of my background, which is why I when I apply for schools, I have to go to a public, in-state school rather than my top choices.

How does it feel to be valedictorian?

RM: I’m first-generation valedictorian, which is cool. It’s really great to make my parents happy. They worked really hard for me to get to this point. I kind of knew since ninth grade that I was going to be valedictorian because my biology honors teacher said, “If I had to guess somebody, it would probably be you.”

Do you consider yourself to be a role model?

RM: I’d like to think so, people look up to me.

What classes do you think would have a significant impact on other Latinx students, were they made available?

RM: I wish that there was a class on Latinx writers, like how’s there one for African-American writers, African studies and whatnot, along with a greater emphasis on Hispanic Heritage Month, like how there’s an emphasis on Black History Month.

Do you have any tips for Latinx or just “of-color” students in regards to achieving academic success?

RM: To all Latinx students: Please stay in school, I know it’s difficult and it gets to be too much. Your parents will still love you even if you have to try some classes again. They will still love you even if you can’t make it to graduation. And they will still love you when you feel that translating back and forth is tiring. Your parents keep telling you that education is important because they did not have the opportunity to [get a full education], but since you have the chance, please don’t take it for granted. Be patient with your parents when explaining how school works; they’re learning too.

As for discrimination and racism, do not let those ignorant words keep you down. We’ve been through enough already, with parents risking their lives to give us a better life to proving those who undermined us wrong. The words will hurt, but we have to stay strong and fight, because we do belong here, we do have a right to become educated, and we will survive.

*Mendoza is non-binary and uses “they/them” pronouns. You can learn more about gender-neutral pronouns here.

**”Latinx” is the gender-neutral variation of Latina/Latino.

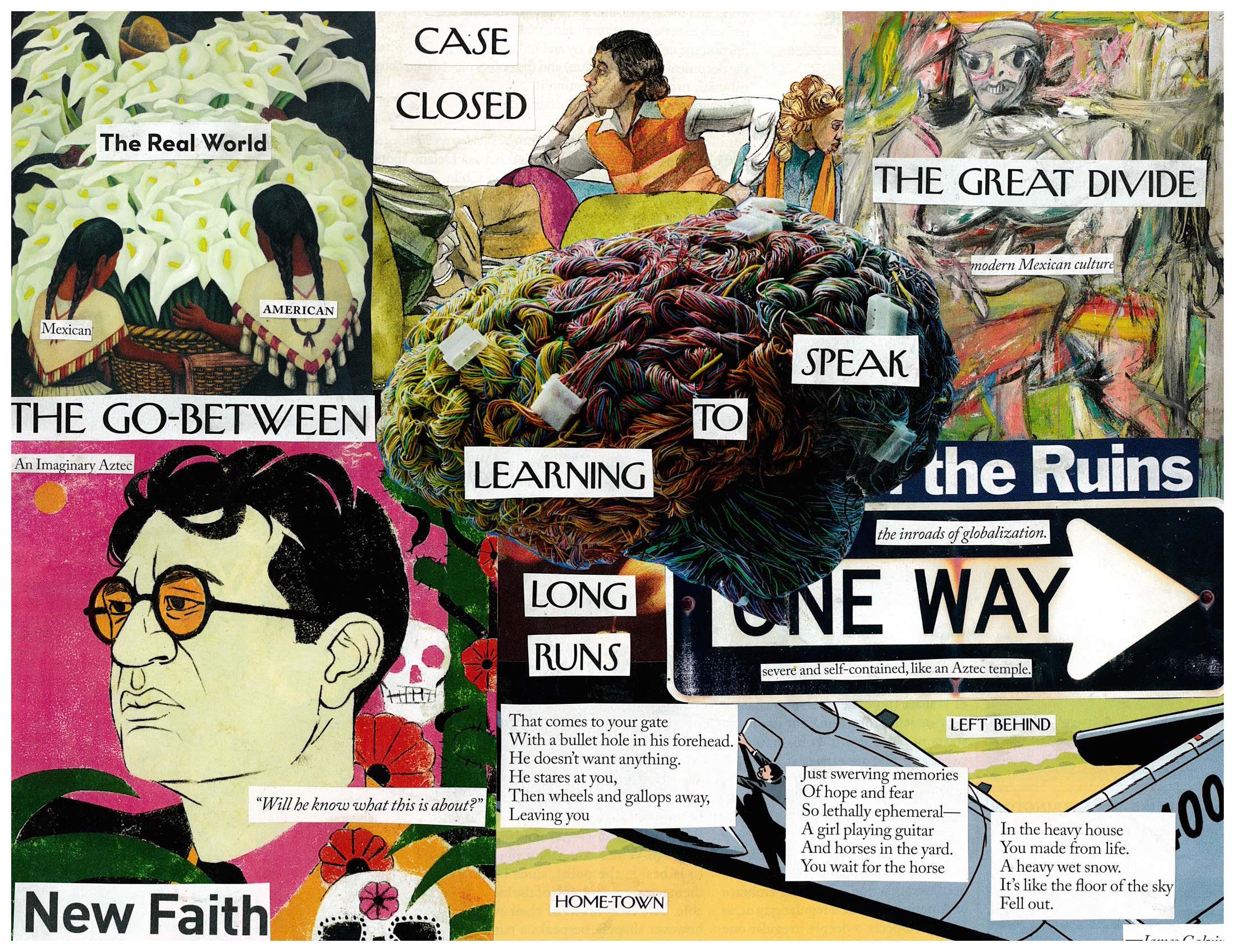

Jahleelah, 16, is a rising senior at Creekside High School who is also an artist and teen activist who is passionate about contemporary art and the underground music scene.

Related Story: Check out these resources for first-generation students.

For more resources for immigrant or first-generation students, try:

Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS) – check out CPACS teens’ published voices here.

Clarkston Community Center Student Success Programs

Latin American Association youth programs

Georgia State University offers a guide for first generation students that includes a timeline from high school to college.