When I was in middle school, I learned about the Children’s Crusades — when school children mobilized to protest unfair segregation laws in 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama, during the height of the civil rights movement. I was amazed. I could barely wrangle all my friends together for a trip to the movies at that time; going head-on against systemic racism was definitely out of the question.

Fifty-five years after the crusades in Alabama, we see teenagers rising up the same way they have for decades. While some adults may consider social media toxic and dangerous to teens, plenty of good can come from teens mobilizing on Instagram or Twitter. With the tap of a button, I can send information to hundreds of teenagers all over Georgia about rallies or other events ranging from various social justice topics of gun prevention to voting rights.

This year saw the birth of March For Our Lives (MFOL), a youth-led movement created in the wake of the Parkland, Florida, shootings last February. Survivors from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School founded the movement and were able to grow it in such a short span of time due to social media. Utilizing the close attention the mainstream media had given the story, they were able to capture the attention of teens across the nation.

As a young black woman, my initial feeling about MFOL was disappointment, not with the movement itself, but rather the way the media decided to tell the story. On March 14, a month after the shooting when thousands of students walked out of schools to protest gun violence, the protest was met with an overwhelmingly positive response from social media and news stations covering it.

What failed to get the same attention was the press conference that a group of black students had. Being that black students make up 11 percent of the population of MSD, there wasn’t a lot of attention on them. During the conference, Tyah-Amoy Roberts said, “We surely do not feel that the lives or voices of minorities are valued as much as those of our white counterparts.” While the conversation started about various gun reforms that would protect students on campus, President Trump made suggestions about arming teachers in order to combat school shooter. However, this idea ignored the reactions expressed about how having more officers on campus would make teens of color more anxious.

Another issue I’ve seen affect teens of color is wondering if they really feel included in the national conversations about gun violence. The National march on March 24 happened in Washington, D.C., and while some teens nationwide were able to attend the event, others like me, coming from a lower economic background, wouldn’t be able to drop everything to go to D.C. for the weekend, even though we feel strongly about the cause. In fact, a Washington Post reporter found 70 percent of MFOL participants were women and 72 percent already had a bachelor’s degree: “Contrary to what’s been reported in many media accounts, the D.C. March for Our Lives crowd was not primarily made up of teenagers. Only about 10 percent of the participants were under 18.”

Another factor that doesn’t help is that rallies and events such as the Road to Change were in areas such as Midtown and Roswell, which are primarily white and affluent. This leaves teens like me to figure out if it’s plausible to go based on lack of transportation or even fear for our safety. I had a large part in planning both of the Georgia Road To Change rallies last summer, and it was challenging for me as an organizer to make it there. The Brian Kemp signs that lined the streets of the location and the Trump 2016 stickers on cars were enough indication for me that I was not welcome in their area. Trying to explain my rationale to the other white attendees was met with sympathy, but I knew that they still truly didn’t understand. That’s not to say when planning the event there weren’t any conversations about making sure the venues were close to MARTA stations; it’s just that they weren’t the top priority.

Morgan Laurio, a 17-year-old black activist from Atlanta who participates in a MFOL Slack group for metro-area teens, agrees that she doesn’t feel included in conversations about gun violence. “I think black activism more often than not is portrayed like a riot or something malevolent,” Laurio wrote to VOX ATL. “Most of society sees black people as violent and aggressive, and that’s how the media portrays [us].”

She compared the way the media portrayed the MFOL movement in contrast with Black Lives Matter: “March For Our Lives was better received by the media,” Laurio said in an email. “The Parkland students still received hate, but the majority of people were on their side. They were trying to protect our students and our future. The Black Lives Matter movement never had a chance. The media chose to ignore the meaning of the movement and think of it like a black supremacist movement. They hate the way people are calling out mistreatment and corruption by police. The media only portrays cops as angels who are trying to protect themselves and the black men they kill as thugs and menaces to society.”

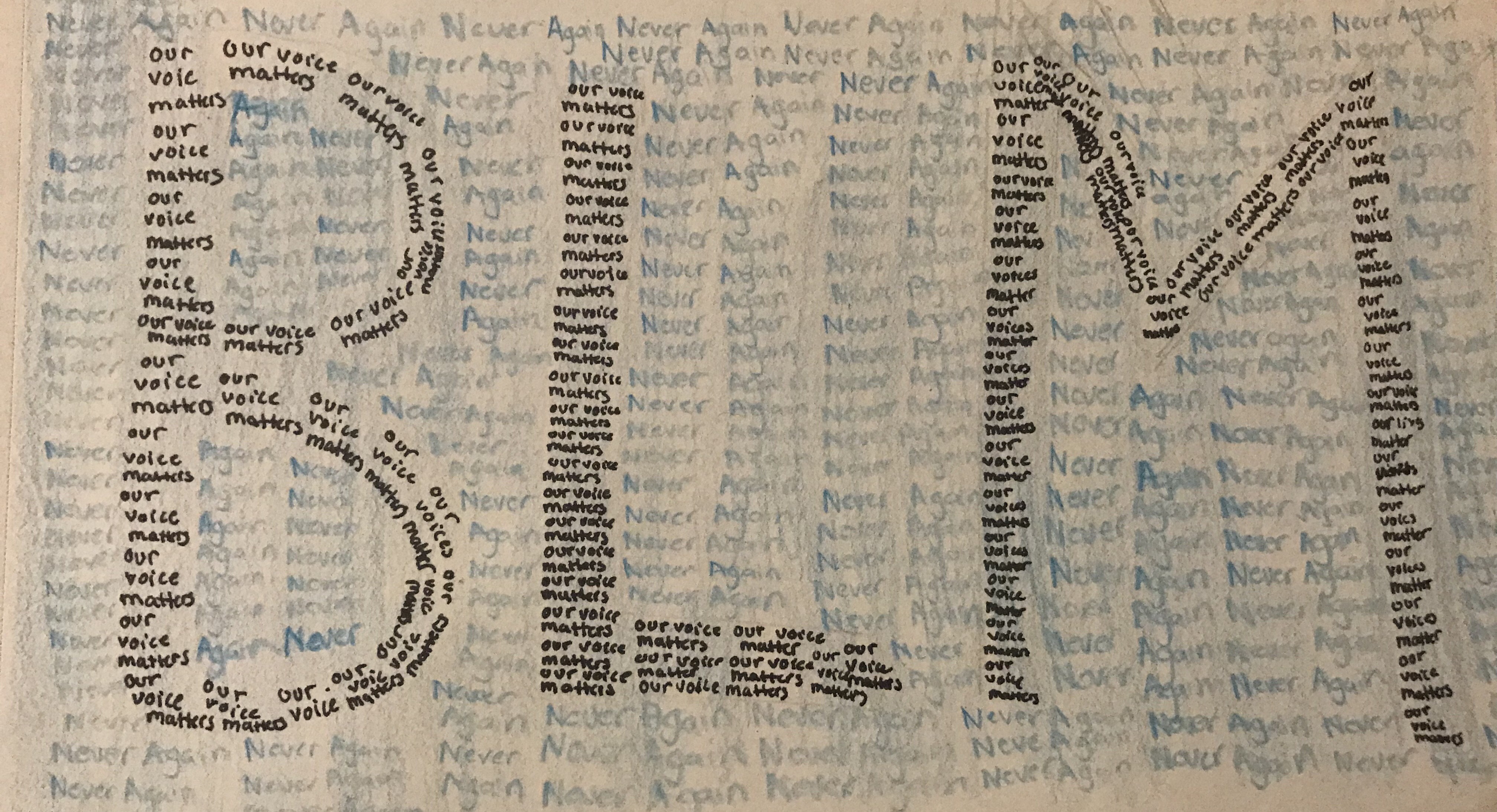

We’ve seen the impact that the #NeverAgain movement has had: Several companies raised the age of gun purchases or even stopped selling them altogether. The double standard of the media describing the MFOL movement as brave and powerful, while ignoring black activists who have been demanding gun reform for years, is a harmful tactic that leaves black youth wondering if our voices even matter.

This isn’t meant to call out the teens at the front of March for Our Lives. I’ve met many of them personally through the work they’ve done on their Road to Change tour this summer. It’s very clear to me that the white teens at the forefront of the movement want to use their privilege to uplift the voices of inner-city youth.

Rather, this is a call out to the mainstream media: You have huge power and influence over what millions of people see every day, and you have inadvertently crafted a narrative showing the only voices that matter in these conversations belong to those who are white. You are further marginalizing our voices. When all I see are white gun violence victims shown as what they are — victims — but the unarmed black boy who was shot and killed deserved it because he was a thug, it shows that black bodies don’t mean anything to you.

Black youth are very well aware that the only reason MFOL got the coverage it did is because it happened in a suburban area. This year, 2018, alone has shown there is a demand for non-white stories to be shared on huge platforms, so now, let’s extend the coverage to non-white voices in this conversation, because our voices matter, too.

Lyric, a 17-year-old homeschooled student, wrote this story because the first result that popped up when she Googled “black teen” was “black teen killed.”