When Former President Barack Obama signed an executive order creating DACA — Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — in 2012, I was a sophomore at Cross Keys High School, a DeKalb County high school located in a majority immigrant community. Conversation about immigration and the threat of deportation was constantly present. I always heard stories of people who had been deported from neighbors and members of the community.

In 2012 DACA gave about 800,000 young people or “DREAMers” a grace period to work, study and live in the U.S. without the threat of deportation. But earlier this month, President Trump’s administration announced a plan to “phase out” DACA benefits while not allowing any new requests after Sept. 5.

What’s DACA?

DACA is a program administered by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (part of the Department of Homeland Security) that temporarily protects certain young people brought to the United States as children (often called “DREAMers”) from deportation and gives them the documentation needed to work or attend school in the U.S.

Young people 15-years old, and under 31, can request DACA, according to USCIS, if you:

-

Were under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012;

-

Came to the United States before reaching your 16th birthday;

-

Have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007, up to the present time;

-

Were physically present in the United States on June 15, 2012, and at the time of making your request for consideration of deferred action with USCIS;

-

Had no lawful status on June 15, 2012;

-

Are currently in school, have graduated or obtained a certificate of completion from high school, have obtained a general education development (GED) certificate, or are an honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or Armed Forces of the United States; and

-

Have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, or three or more other misdemeanors, and do not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety.

Why DACA matters

After DACA, there was a sense of hope for an immigration reform among my classmates and community members. Parents of DACA recipients thought it would be easier for their children to reach the American dream. Before DACA, I did not even know some of my classmates were undocumented. They participated in the same school clubs and sports; they were like any typical high school student — except for their legal status. DACA gave teenagers the comfort to talk about their status. They were able to have documentation and speak up without the fear of deportation as a way of retaliation. They were no longer ashamed of their status.

When the conversation about DACA is brought up today, people do not realize how close they can be to a DACA recipient. DACA is not a distant political issue. As of last March, more than 50,000 Georgians had requested consideration under DACA — and more than 45,000 were approved (many of these are renewals, since DACA provides benefits on a two-year basis). Georgia ranks 10th highest in the country in number of DACA recipients. It is important to have a public conversation to eliminate the distance some people feel with this issue.

Creating public awareness

Now, I am a junior at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, and a staff writer for Mercer University’s student-run newspaper The Cluster, where I write regularly.

The editors and staff became interested in covering DACA when word got around that some Mercer students would be impacted by the potential termination of the program. Reporting on DACA led me to meet Eduardo Rubio.

Rubio is a Mercer sophomore who is triple-majoring in economics, math and computer science — and is a DACA recipient.

Rubio revealed his status as a DACA recipient on social media to spread awareness. I met him for the first time to interview him for an article to add a personal perspective on the potential termination of DACA. His voice would allow Mercer students to be made aware of the issue and realize how they are connected to it.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, there are about 47,000 DACA immediately eligible people in Georgia, making up 4 percent of the national DACA population. According to Educators for Fair Consideration, about 65,000 undocumented students who have lived in the U.S. for more than five years graduate high school each year, and 7,000 to 13,000 undocumented students enroll in U.S. colleges.

“[DACA] allows immigrants who came as children, such as me, a shot at normal American life. [It allows us to] get a social security number, [which then] allows us to get [a] driver’s license and a workers permit,” Rubio said.

Rubio said he always knew he wasn’t from the United States. Rubio was born in Mexico and was brought to the United States when he was 4 years old in hopes of helping his younger brother receive better treatment opportunities for autism. However, it wasn’t until his sophomore year of high school when he realized what being undocumented meant for him and others in his situation.

“Junior and sophomore year of high school is when everybody starts getting their driver’s license, [and] the conversation of college starts picking up,” Rubio said. “I remember seeing all my friends be able to do all these things I wasn’t able to.”

According to the U.S. Department of Education, DACA recipients are not eligible for federally funded financial aid, including loans, grants and scholarships. DACA recipients also have to pay out-of-state tuition at public institutions. Twenty-one states allow them to pay in-state tuition; however, Georgia is not one of those states.

“The financial barriers are enormous, so for a really long time I did not think I would be able to go to college at all,” Rubio said.

Mercer University is a private institution; therefore, DACA recipients like Rubio can receive merit-based and other private scholarships, like other students. The number of DACA recipients attending Mercer is not known since the private institution does not require students to disclose this information during the admissions process, according to Mercer’s admissions department.

So, why end DACA?

President Trump’s administration says DACA is an overreach of power.

“DACA was effectuated by the previous administration through executive action, without proper statutory authority and with no established end-date, after Congress’ repeated rejection of proposed legislation that would have accomplished a similar result,” said U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions in a public letter to Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Elaine Duke. “Such an open-ended circumvention of immigration laws was an unconstitutional exercise of authority by the Executive Branch.”

In the announcement, the Trump administration said there is a six-month delay on the termination of DACA, giving time for Congress to vote to make a long term legislative decision. “Dreamers” and other advocates are pushing for the approval of Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, also known as the DREAM Act, which was introduced to the U.S. Senate in 2001 and has been rejected several times.

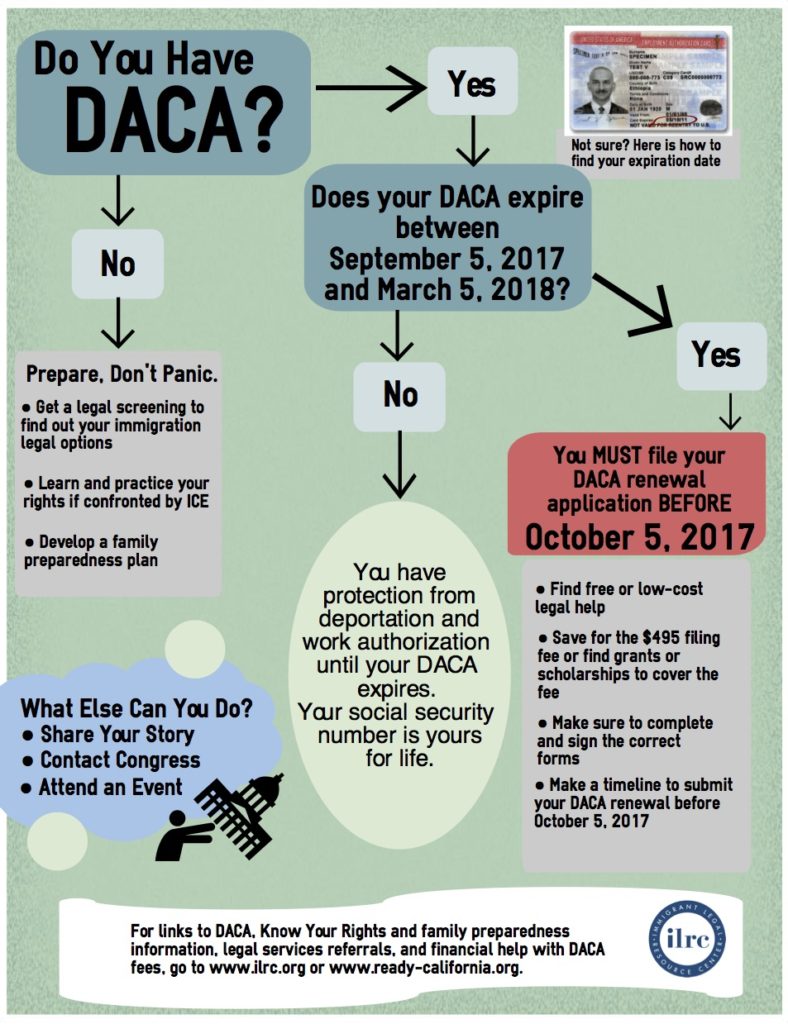

What this announcement means for DACA recipients

“It’s terrifying, it’s disheartening. I think of my little brother. He is 16 years old, and he has autism. If he were to be deported, I don’t know what we would do,” Rubio said.

DACA recipients are our classmates, co-workers, friends, neighbors, etc. We can no longer afford to be silent on issues that do not directly impact us. Some DACA recipients may be afraid to speak up.

If you’re interested in fighting for DACA, you can get involved with community organizations such as Georgia Undocumented Youth Alliance. You can also text RESIST to 50409 to tell your representatives how you feel about DACA.

Vanessa, 20, is a junior studying political science and journalism, and is an alumna of VOX, where she served as a writer and workshop facilitator while attending Cross Keys High School.

Photo: Eduadro Rubio (left) and his younger brother

Editor’s note:

For more info about DACA, check out the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, which offers information and resources in English and Spanish.

VOX will cover immigration and the experiences of refugee teens all semester — and we invite your stories, opinions and art. Email editor@voxatl.org!

Save the date! Share your voice – Dec. 9.

Save the date! Share your voice – Dec. 9.

This semester we invite you to join VOX teens in a community dialogue about immigration. Create art. Slam poetry. Meet each other. Follow along this semester’s investigation voxatl.org/category/vox-investigates/.